On Rewrites, Noir, and Transgression in a Post-Deviance Age

And also — a special audio track.

Welcome back, my little gremlins — to The Boneyard. This is my place to talk about arts and craft.

This, and other pieces like it, are expanding on my in-text ‘director’s commentary’ in Electric Love. That part — and the story itself — is available for free. This, and additional things I write that adds to the story, are for my paid subscribers — the Secret Revengers Club.

If you aren’t a paid subscriber and don’t want to miss out — don’t worry. All these essays will be put together and published when ITFTVS is complete, for a one-time payment.

First — a little bit of special love for my Secret Revengers. A just-for-fun track from me and the greatest band in all the land: The Electric Kool-Aid Stand.

I had this idea for a song for Electric Love with a little bit of a Bond film vibe — and decided to put this one together. It’s unlisted on YouTube — it’s just for all of you who support my work.

I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it.

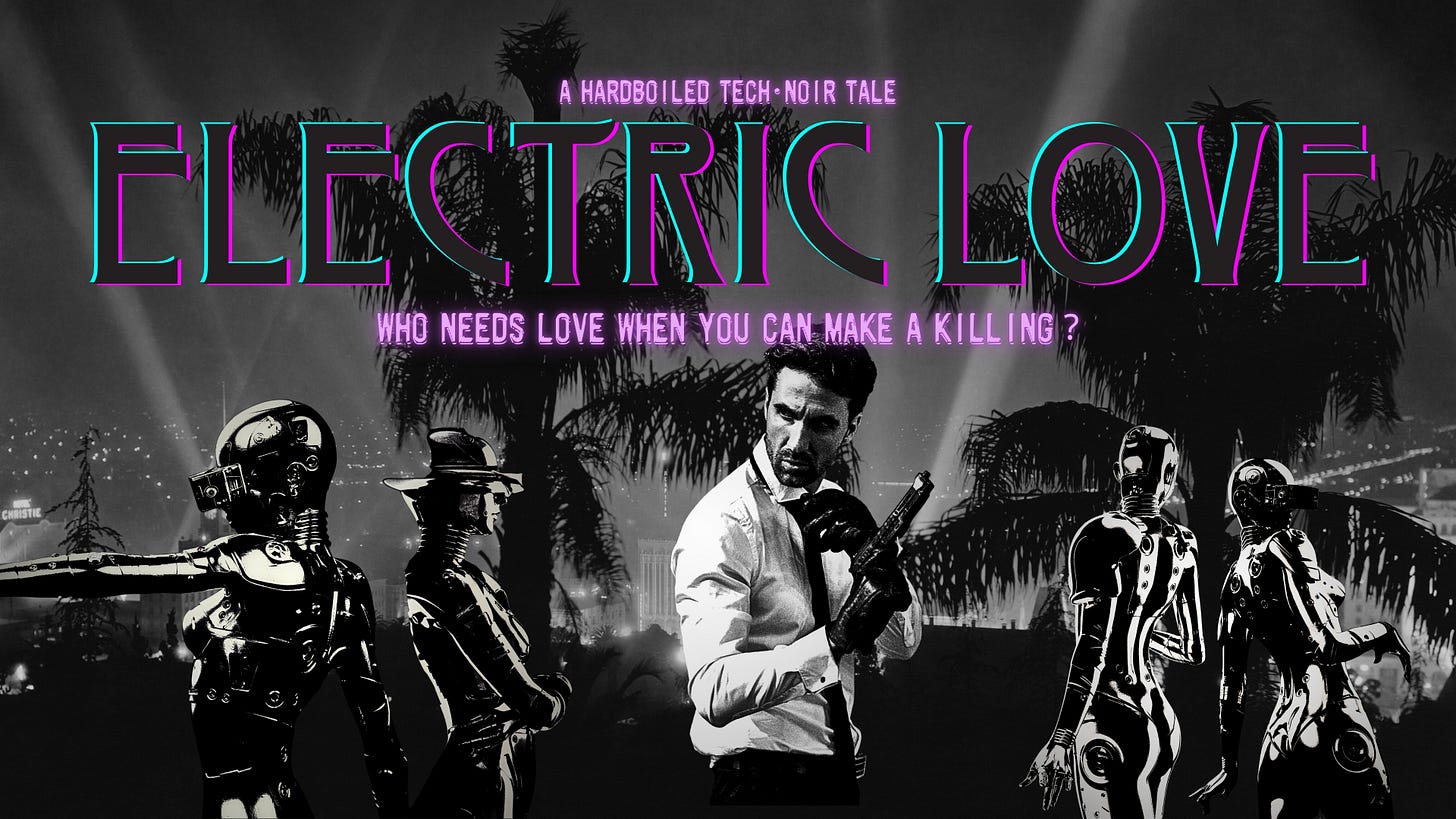

This is going to be something of a brain dump, and it will need a little background on a serial I’m running called Electric Love. You can check out the [insert coin] post about it here for all the details, but the short version is this:

The concept was originally a spin-off of another (and longer-term) project called [ignition girl] (and you can find the prologue to that one here). The main character of Electric Love is a side character in [ignition girl].

It was originally conceived as a more straightforward story set in the same universe as [ignition girl] (because [ignition girl] is more experimental, and because I like the world I built for it.

It’s what it says on the tin: it’s meant to be a hardboiled tech-noir story in the vein of some of my favorite authors: Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett — just updated to my cyberpunk-noir setting and more in my own voice.

Something you need to know about me —

There comes a time, in everything I write, in which I decide how much I hate what I’m working on.

That point is roughly at the end of the first act of the story. As I do with just about everything — I reached that point in Electric Love and had to ask myself:

Why do I hate this?

There’s always something I don’t like about my first acts, and it’s rarely the same thing. This time it has a lot to do with the tone and style I’m working in. Namely:

It has a somewhat…”brighter” tone than [ignition girl], and that’s going to make it difficult to mesh well into the overarching setting narrative.

I have a soft spot for transgressive literature, especially when it comes to the hardboiled/noir tradition — but I also have…opinions about the state of transgressive literature.

The latter has been more on my mind lately, especially after reading Adam Mastroianni’s (of Experimental History here on Substack) “The Decline of Deviance,” this week.

Particularly the part about sculptor Arturo di Modica (of the Wall Street Charging Bull) and the more commercial, sanitized-yet-nominally defiant Fearless Girl, installed in 2017.

Adam contrasted the original intent of Di Modica:

My point was to show people that if you want to do something in a moment things are very bad, you can do it. You can do it by yourself. My point was that you must be strong.

with the commercial statement of Fearless Girl (advertising for a hedge fund, basically).

That, as things do, made me think of Foucault’s “A Preface to Transgression” (if you want a copy, I’ve got you covered).

Foucault used George Bataille’s “Story of the Eye” (as Barthes would elsewhere) to talk about transgression in fiction.

You don’t need to know all of the context there (unless you want to go for a deep dive) — I’ll summarize for you.

transgressive means “violating social boundaries or morals,” or, sometimes “good taste.”

it’s generally agreed that transgressive fiction (in so much as it even can be considered a) genre is (of course) fiction that explores things outside the boundaries of “good taste.”

Transgression deals in all kinds of taboos — from graphic violence (a well-worn hallmark of the hardboiled noir tradition), to body horror, to splatterpunk, themes of rape, incest, drug use, dysfunctional relationships, kinks, and so on.

As topics of sex go — the line of demarcation between smut and transgression is how horny it is.

Smut (or “erotica,” if you’re feeling fancy) is designed to arouse. To titillate. To make you horny.

Transgressive sex in literature tends to take a more Brechtian (or Ibsenian) approach to sex — and often uses alienation to prop up a disconnect between the audience and arousal.

That’s not always true. There have been transgressive writers (especially in bizarro) that blur the line between transgressive sex and erotica in literature.

Transgression has also always been a staple of the hardboiled and noir traditions, because transgression is, by its nature, experiential.

It’s a search for truths in the darkness of humanity.

A perfect fit for the Sam Spades and Phillip Marlowes of the world.

Which brings me back to “The Decline of Deviance.”

Because, in a world where social deviance is declining and a world long past the Sexual Revolution and normalizing of kink, of homosexuality, transexuality, and so on (whether it’s to an ideal or not is subjective — it remains objective that conditions are better for those living their lives than in the days of, say, Chandler and Hammett) — it begs a question:

What’s transgressive anymore?

American Psychos, Pisschrist, and Sadgirls

Since we’re talking about Electric Love, a kind of detective story — let’s talk about Raymond Chandler.

Chandler isn’t generally thought of as a transgressive fiction author.

I’d argue there’s really no such thing as transgressive fiction as a genre, even if there are writers who do skew more broadly transgressive. A few of them are here on Substack: Chandler Morrison, Elle Nash, and so on.

We’ll also talk about them.

Morrison does a lot of dark satirical social commentary. His stuff works with themes of death, individuality, and generational identity.

Nash works with an unsentimental view of sex, violence, and poverty/class issues.

Transgressive literature always has a sense of social commentary — and the general line between fiction that’s transgressive and, say, bizarro (the realm of writers like Carlton Mellick), is how much leans into shock value for its own sake.

Chandler did similar things, in a way that was somewhat transgressive for his time. The unsentimental look at the world’s darkness and corruption (and sex, and murder) was different from what many of his contemporaries were working with.

The distinction that came to be known as “hardboiled fiction,” that’s often pastiched to this day (ironically losing what made it hardboiled in the first place) comes down to this:

A cynical worldview, usually from the protagonist’s POV.

Gritty (or at least grounded) realism.

Social commentary, usually on political corruption, sex, and the nature of violence/the predisposition of people to violence. (Chandler and Hammett both did all of these)

It was a reaction to “cozy” styles of upper-class protagonists — think Conan Doyle and Christie’s work (though Agatha is misunderstood to this day in how dark some of her work actually is1

It’s hard-edged and unsentimental.

See my point?

In their day — hardboiled detective story writers were being transgressive.

Today, it’s easy to make pastiches of hardboiled and the noir2 style that came from it. Times have changed — the kinds of things that Chandler write about in The Big Sleep (a gay pornographer) or Hammett did in Red Harvest3 (union busting, violence) are much more normal in fiction today — modern crime writers like Michael Connelly, or some of the 20th century greats like James M. Cain and Lawrence Block, have stories heavily indebted to the tradition.

Serial killers aren’t the social taboo they once were. People didn’t talk about them, and headlines scandalized it. Now? Your local true crime girlypop™ can tell you all you ever wanted to know about Ed Gein and the Night Stalker.

Even things like Morrison and Nash have written about — eating disorders — aren’t as taboo as they once were.

Transgression requires deviance, requires taboos. Coloring outside the lines doesn’t matter when the lines have blurred to the point nobody notices them anymore.

Which is why, in turn, a lot of transgressive fiction (even the classics from Burroughs and Burgess, say) read more today as shock value titles, or worse — schlocky.

It’s the commercialization of Piss Christ,4 in a way Warhol could only wet-dream about.

It’s the aesthetic of transgression, without the substance (or what Baudrillard would call a simulacrum of transgression — an imitation of a thing that feels more real than the thing itself).

Which is something I have to engage with in my work — because I do want Electric Love (and the broader [ignition girl] story) to deal with darker things, in unsentimental, unromantic ways. I do want to experiment with pushing the envelope further in service to the stories themselves.

Even if that’s a difficult thing to engage with in a time when the world has filled gaps in which deviance used to hide in.

An homogenized world is a difficult one to be transgressive in.

And maybe that’s the point, really:

To be transgressive today might mean engaging with different kinds of social norms — anti-intellectualism (or intellectualism itself). Identity itself (which the [ignition girl] world does, by design, deal with). Sexuality and how we perceive it less so than the act of engaging in it. How we emotionally and mentally relate to sex. The conceptualizing of sex, violence — and taboos themselves.

Because, in a time that feels like it has less room than ever for meaningful transgression in fiction —

Perhaps the greatest transgressive act is questioning what it even means anymore.

I could write a whole piece on how Murder on the Orient Express works as well as it does because of the confining atmosphere she builds in the book; and a recurring theme of hers of upper-class opulence and the pretenses that come with it are suffocating. She builds her Orient Express as a metaphor for that.

The difference in hardboiled and noir is mostly in the ending. Hardboiled protagonists tend to solve their cases and get a “happy for now” ending out of it, at least. Noir tends to be a full downer ending, at least in fiction. Film noir is a specific kind of aesthetic in addition to being (usually) hardboiled or crime noir.

Everyone remembers Sam Spade, but his Continental Op is criminally (pun absolutely intended) underrated. As is, of course, the First Couple of crime fiction — Nick and Nora Charles (their dog is the namesake of the Asta-Charles Hotel in Electric Love).

Andres Serrano’s artwork, technically called Immersion (Piss Christ) — a wood and plastic crucifix submerged in Serrano’s, well, piss, and photographed.